Protocol Test for Fiction

The Bechdel Test for system-based fiction

A Framework for System-Based Storytelling

Chiang’s Law states that sci-fi is about special rules, and fantasy is about special people.

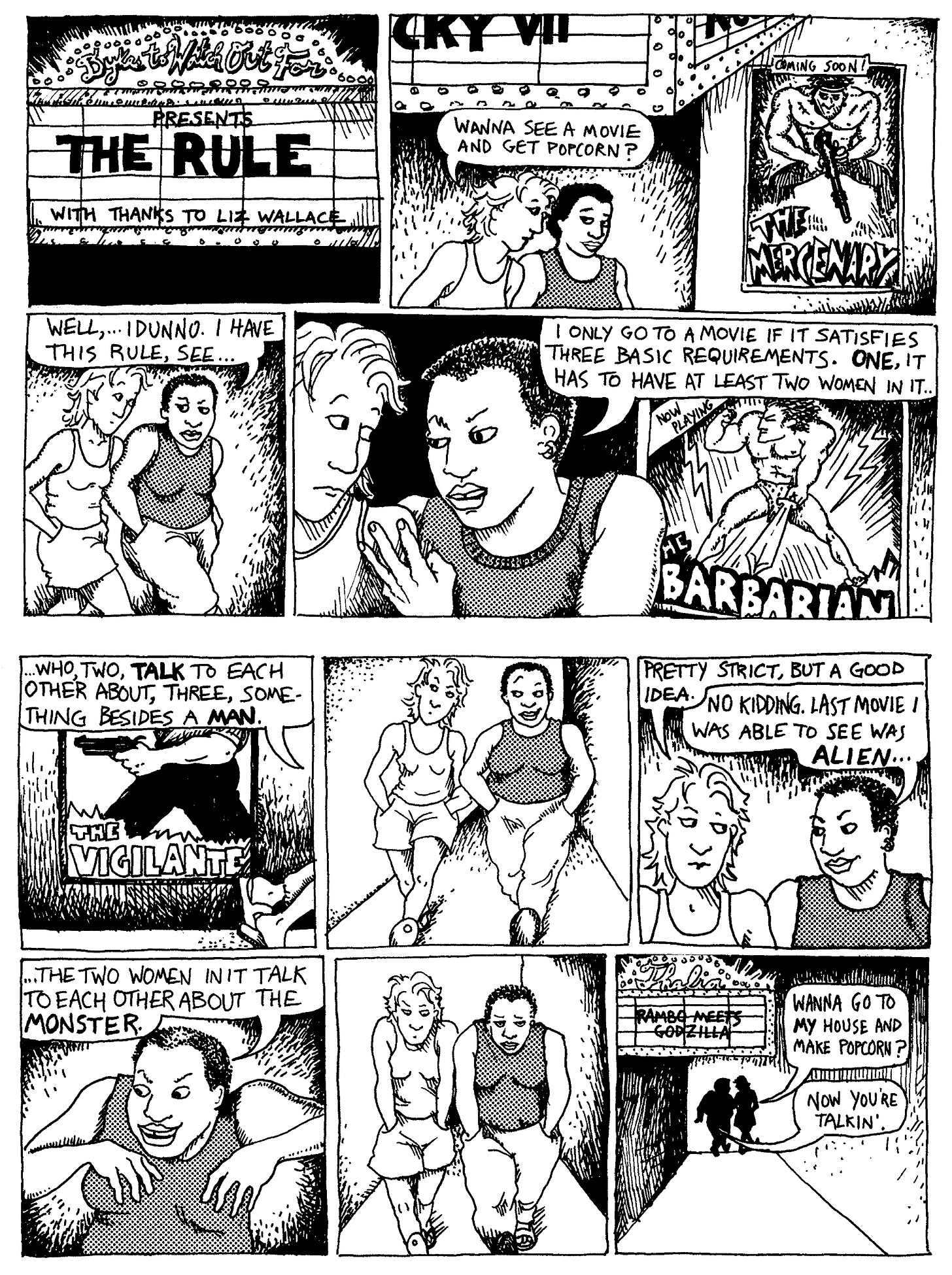

In 1986, the Bechdel Test1 emerged as a simple but powerful tool to evaluate female representation in movies. It asked three basic questions: (1) Are there at least two women? (2) Do they talk to each other? (3) About something besides a man?

So how might we create a similar test for Chiang’s Law?

Credit for this idea goes to

from this talk on “A Protocol Fiction Protocol” [01:04:34] and , from the talk and the Protocolized Discord.2The core question

Is the agency of the protagonist greater than the agency of the system, or vice versa?

When a protagonist's agency is greater, we're in the realm of fantasy or what we might call "Great Man Fiction."

The fictional world revolves around one central character whose special qualities drive the story.

When the system's agency is greater, we're in the realm of science fiction or "Protocol Fiction."

Here, the fictional world is merely illustrated through a particular character who could be replaced without breaking the narrative.

Protocol Fiction Test

1 - The same exact plotline could plausibly happen to two, one hundred, or one thousand people in the system without breaking the narrative

2 - Someone with a different set of experiences could play the same plot roles

Another way to put this might be: if you didn’t build it, someone else would come along and build it.

3 - A key property of systems is resilience - one particular person’s actions aren’t enough to change the rules

In the spirit of the Bechdel Test3, let’s reframe this a bit into one sentence:

1 - The same plotline could have happened to multiple people simultaneously

2 - Who could have been replaced in any of their plot functions by someone else

3 - None of whom alone are enough to reshape the system

Why is this important?

We currently live in an era dominated by "great man" stories. Self-proclaimed exceptional individuals shape our cultural narratives and often wreak havoc in the process.

What we need are more stories about systems and how ordinary people navigate them and make change within them. How can ordinary people win our sympathy and be heroic or damned, in their own ways, on their own terms?

Using the Test

Let's examine how different stories hold up against this test:

Lord of the Rings: Fantasy/"Great Man Fiction"

1 - The plotline could only happen to him. There is only one ring and he has it

2 - Frodo is only able to have the adventure because of his relationship to Bilbo

3 - Frodo's actions directly change the rules of Middle-earth

Blade Runner 2049: Science Fiction/"Protocol Fiction"

In contrast, in Blade Runner 2049, you can imagine that Rick Deckard is only one of many humans who have unknowingly fathered children with replicants. We become invested in his particular arc, but it’s much less about that than it is about the human-replicant relations overall.

1 - K/Joe is just one of many replicants; Deckard is just one of potentially many humans who fathered children with replicants

2 - Someone who didn’t have Rick Deckard’s or K/Joe’s exact experiences could also find themselves in the same moral quandary

3 - No individual character's actions fundamentally change the human-replicant social structure

One of the key utilities of having a test like this is that it extends Chiang’s Law beyond sci-fi vs fantasy to ‘protagonist fiction’ vs ‘protocol fiction’ more broadly.

Here are a few examples where we’re neither in a sci-fi nor in a fantasy context, but we can make some interesting statements about protagonist vs protocol:

Emma: "Protocol Fiction"

Jane Austen’s Emma is like this too. You can imagine that there were many socialites facing similar circumstances and constraints.

1 - Any number of rich socialites could get into matchmaking in the early 1800s

2 - Someone who hadn’t introduced the specific couple that the titular Emma does could still fall into the same predicament

3 - No matter what Emma does – if she marries, doesn’t, has a child out of wedlock – none of it would affect the structure of her overall British village Highbury or of Regency England.

Gone with the Wind: "Protocol Fiction"

Gone with the Wind is about antebellum American society and one particular plantation heiress turned scheming business owner, but fundamentally she’s a small-time player. The Civil War, and Reconstruction, would have happened with or without her.

1 - There are plausibly other scheming socialites

2 - Someone who didn’t inherit the exact plantation Scarlett does could have the same things happen to her

3 - Her actions alone don’t change anyone’s mind

Stories For This Moment

Defining Protocol Fiction as a genre is fundamentally about creating more relatable, more relevant heroes, to help us tell ourselves the stories we need to hear. These narratives might better reflect our lived experience in a world where individual agency exists within—and is often constrained by—larger social, economic, and political frameworks.

In an era where "great man" narratives dominate our cultural landscape—from superhero blockbusters to tech billionaire biographies—protocol fiction offers a necessary counterbalance.

Let me know in the comments if you find other interesting examples or non-examples.

Originally, the Bechdel Test was a comic called “The Rule” appearing in Allison Bechdel’s comic strip Dykes to Watch Out For

The original Bechdel test restated into its three principles for readability:

1 - It has to have at least two women in it

2 - Who talk to each other

3 - About something other than a man

Interesting article. I'm not sure I've found any difficulty in telling fantasy from science fiction, though.

I like this framing.

The movie “Twelve angry men” stands out as almost the epitomy of being about protocol, even though the protagonist has to work with his own character’s individual gift of persuasion. But the movie is really about protocol.

Movies not about protocol are legion and I tend to find them boring.

There are also movies such as the James Bond series, where a particular character is working a fantasy story, but as a protocolized, abstract character. So this is potentially an example of a hybrid between protocol and fantasy. The Bond standard storyline is protocol even though each individual story is hero fantasy.

I for once would love to see a Bond movie where Bond hits protocol as his limit - where he fails, overcomes, fails, overcomes. Closest candidate to such a movie is the Craig version of Casino Royale, which is why I liked it so much. Thanks to your framing here I now understand why so many people, inexplicably to me at the time, did not like it: too much protocol, not enough fantasy.

Spy stories of protocol: John Le Carre, best example Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy. Systems fight systems, individuals are crushed interchangeably.